La Londe-les-Maures and Les Bormettes

Les Bormettes is one of the oldest place names in the costal area of Var. It goes back to the time when the Bormani, a Celto-Ligurian tribe, settled on the coast. The name now only relates to a district of La Londe, but once it corresponded to a much larger territory, bounded by the Bormes communes to the east, La Garde to the west, Pignans to the north and the sea to the south.

The first traces of human settlement in this district date back to Roman times. According to excavations of the late nineteenth century, the Romans had built a farm at the foot of Hospital Hill. The discovery of millstocks, amphorae and other items testify to farming by the Romans of wheat, olives and wine.

In the Middle Ages, St Martin’s tower which dominates the wine-making castle of Bormettes was built and it seems to have sheltered the first village of La Londe. It appears first to have been a defensive site built by the Ligurians, in the 7th-6th centuries BC, against the Phoenicians raided the coast from the beginning of the Iron Age, perhaps to exploit lead and silver mines. By the 13th Century, St. Martin’s Tower was a fortified site. The village would have been somewhat more transient but would have developed around the castle hill.

On Hospital Hill, near St Martin’s Tower, it is likely that there was a Hospital set up by the Hospitallers of the Order of St. John, to cure crusaders, unless it was one of those leprosaria built in the 7th Century at the time when leprosy was wreaking havoc in Provence. The only trace we have is a watercolour painted by a native of La Londe just before the last vestiges were destroyed by the German armies in 1943. It seems to be a monastic building. A local legend seems to confirm that it was a crusader hospital. The location of this hospital between the beach of Pellegrin (Pellerin) and the Templar Tower in Hyères seems quite justified.

From the 11th Century, Les Bormettes gradually became monastic property, with the birth of the monasteries of Montrieux and La Verne. The monks acquired land and developed farms which were then tenanted out. Les Bormettes’ income went primarily to the Chartreuse de la Verne, they pursued an aggressive land purchase policy which inevitably led to conflict with the monks of Montrieux. Apparently, boundary markers can still be found that mark the boundaries of the land owned by each monastic house. At the end of the 16th century, following the destruction of their chartreuse, the monks of Montrieux withdrew from Les Bormettes. The monks of La Verne then asserted control and built the first of their castles: Les Bormettes between 1588 and 1642 and then that of Bastidon.

These two areas complemented each other. One cultivated wheat, oats and artichokes and one practiced dairy farming and poultry, Les Bormettes also remained as an area of vineayrds while Bastidon that of mulberry and olive trees. The olives of Bastidon were brought to Les Bormettes where the monks had installed an important oil mill in 1704 which provded a significant income to the monastery. According to an inventory of 1790, the fields around Les Bormettes produced 51 urns of nearly 130 hl of oil and 20 barrels of 380 hl of wine.

In 1707, during the War of Spanish Succession, the estate of Les Bormettes was plundered by the Anglo-Dutch, they destroyed produce and torched buildings.

The estate remained in the hands of the Carthusians until 1791. There was little human habitiation until the Revolution. Nationalisation occurred at the Revolution and the land was auctioned off. Pierre Laure, cousin of Joseph Laure who would be the 1st mayor of Londe, acquired the estate. Then in 1855, Horace Vernet (1789-1863) took ownership.

The estate remained in the hands of the Carthusians until 1791. There was little human habitiation until the Revolution. Nationalisation occurred at the Revolution and the land was auctioned off. Pierre Laure, cousin of Joseph Laure who would be the 1st mayor of Londe, acquired the estate. Then in 1855, Horace Vernet (1789-1863) took ownership.

He was attracted by the warmer winter weather of Hyères in the Côte d’Azur. Les Bormettes reminded him of the landscape of Algeria that he immortalized in his paintings. Suffering from pleurisy and anxious to find calm to pass his final years, he purchased the estate and built an eclectically style castle, which he felt appeared a little like a village. He built a chapel, dedicated to Saint Victor, in memory of the monks of Marseille who owned the land in the 11th Century.

He was attracted by the warmer winter weather of Hyères in the Côte d’Azur. Les Bormettes reminded him of the landscape of Algeria that he immortalized in his paintings. Suffering from pleurisy and anxious to find calm to pass his final years, he purchased the estate and built an eclectically style castle, which he felt appeared a little like a village. He built a chapel, dedicated to Saint Victor, in memory of the monks of Marseille who owned the land in the 11th Century.

In 1874, Victor Roux, a wealthy Marseille financier, bought the estate. He restored the castle and developed the estate, planting a wide variety of palms, mimosas and eucalyptus, which made it one of the most beautiful parks of the coast.

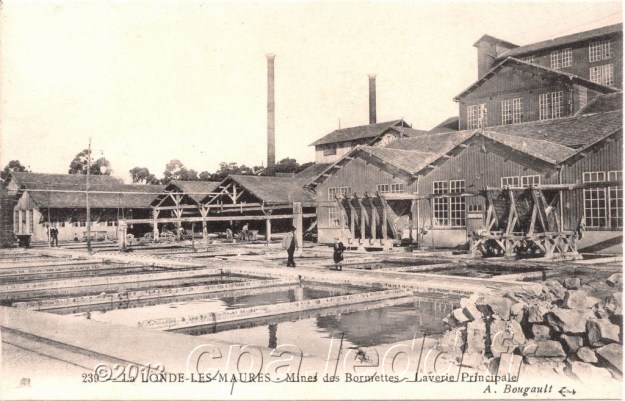

In 1890, he further enlarged the castle and developed the mining in the area., One sign of the prosperity of the estate is the foundry which processed mineral ore locally and so significantly increased its export value.

The mines were very prosperous until the turn of the 20th Century. The richest vein became exhausted and by 1929 all activity had ceased.

But in their heyday, the mines contributed dramatically to the local economy. They resulted in a significant increase in the local population and the development of the small village of La Londe into a town. The town even gave itself a longer name when it formally became a municipality independent of Hyères – ‘La Londe les Maures’.

The Mines of Les Bormettes and their Railways

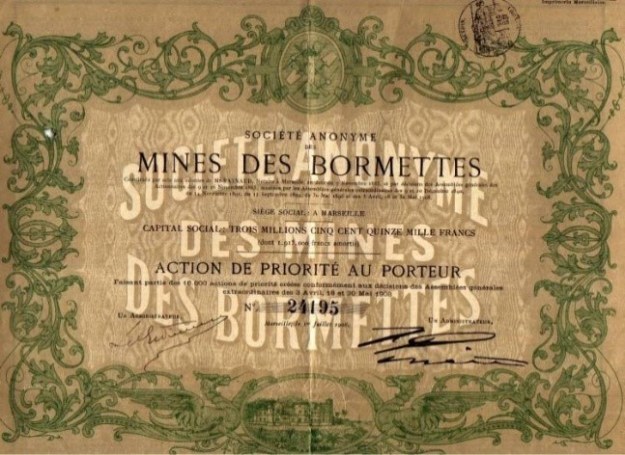

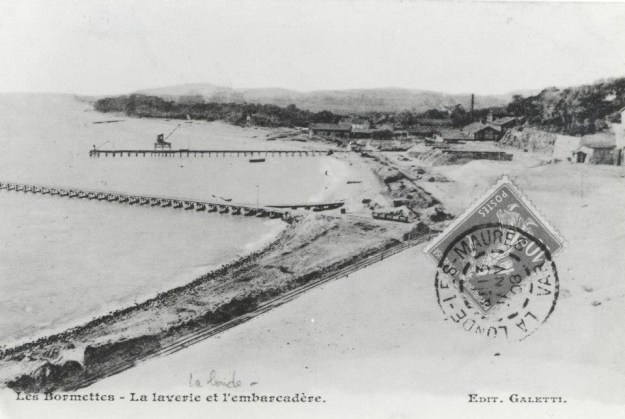

Around 1875, Victor Roux rediscovered a silver-lead vein on his estate and, a few years later, he created a company to mine the vein. From 1890, other veins were discovered north of La Londe and were also exploited. At the same time the mainline narrow gauge railway from Hyères to Fréjus completed and Victor Roux developed a line which extended from Les Bormettes in the South through La Londe to the mines he was developing North of the town. The railway connected the extraction wells, the treatment workshops, the Argentière pier and the Hyères-Fréjus line. The opposition of the villagers delayed the construction of the most important section between the extraction sites of the north of the commune, the processing plant and the pier until 1899. The veins of minerals in the mines were quickly exhausted and the exploitation of the mines began to decline in 1904 and ceased completely in 1929.

On the hand drawn plan above the route of the mining railway is shown in blue. This does not do justice to the full extent of the system developed by Victor Roux, although the railway north of La Monde on the 1930s Michelin map below would only have been in use from 1899 to 1929.

It is possible to identify the location of the original mines near the sea-shore on both maps, and the location of the foundry. On the map immediately above, the locations of the Verger Mine and the La Rieille are well marked. Using the hand drawn map, it is relatively easy to determine the alignment of the railway tracks close to the coast. It appears that the foundry buildings are now in use as a hotel known as Les Grottes.

It is possible to identify the location of the original mines near the sea-shore on both maps, and the location of the foundry. On the map immediately above, the locations of the Verger Mine and the La Rieille are well marked. Using the hand drawn map, it is relatively easy to determine the alignment of the railway tracks close to the coast. It appears that the foundry buildings are now in use as a hotel known as Les Grottes.

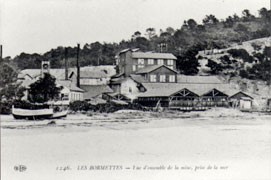

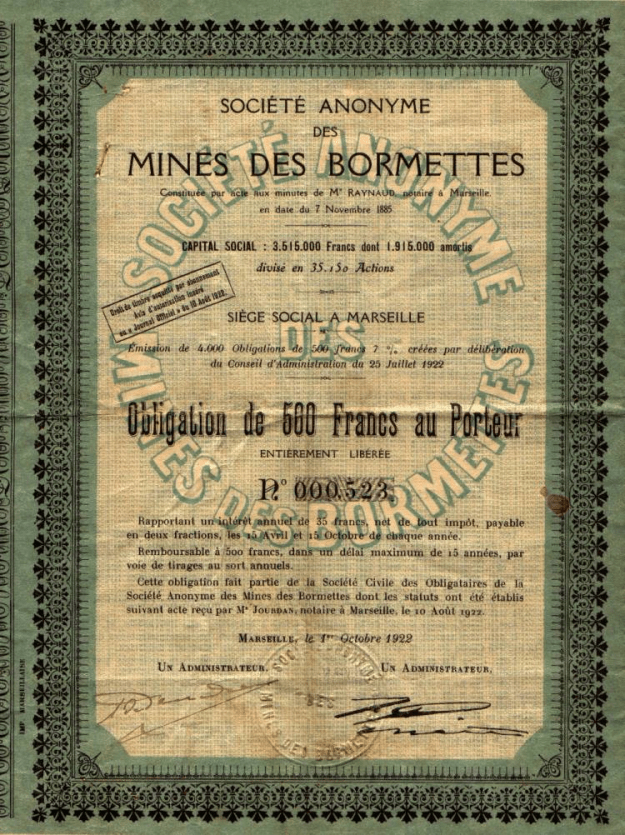

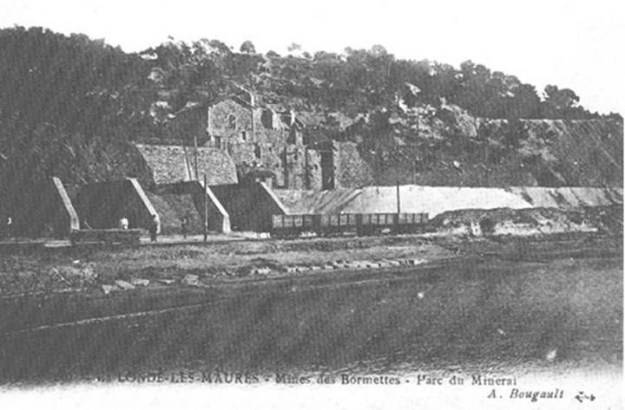

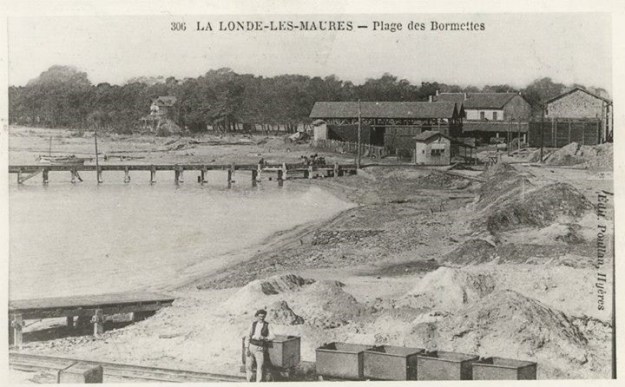

I believe that these certificates are shares in the mining company issued at different times 1908, 1922 and 1924. Apart from the first of these images, which is of the foundry, the photographs are of the mine at Les Bormettes and show also the loading jetty to allow minerals to be removed by sea. The dependence on rail, either within the site or for transport to other rail heads is evident in the pictures.

There is evidence of the route of the older railway in the layout of the roads between La Londe and the coast. It is very difficult to find substantive evidence of the railway north of La Londe. The D88 follows the River Pansard on its West bank, there are sporadic lengths of what may well have been the track-bed of the old railway on the East bank of the river. I did not find evidence of a bridge carrying a branch over the river toward what appears to be the location of the Mine du Verger. It is nearly 80 years since the line closed, so perhaps this is not at all surprising. Three pictures of the mine location appear below, these are taken from the mine data site mindat.org [3]. The first two are of the spoil heaps the third is of the mine location.

Mindat.org also provides details of what remains at La Rieille Mine [4] further up the valley of the Pansard and the terminus of the railway. Three photos again. This time the remains are a little more significant.

These last two images (below) before we turn away from the mining operation to focus on the munitions factory show the old jetty alongside the new office building. In the second image the camera has turned to look slightly further to the West and the factory building can be seen behind the offices. The photographs must have been taken after 1913. As the jetty appears still to be in use they cannot date from after 1929.

A little careful study of the image below will reveal much of the layout of the old mineral railway. It also shows the location of the Munitions Factory set up by Schneider – the large building just left of centre at the bottom of the picture.

And finally a link to a presentation about the mines (in French) – http://slideplayer.fr/slide/1157478.

The Munitions Factory at Les Bormettes and its Railway

At the time when mining activity was declining, the local economy was rescued by the arrival of the Schneider Company. Schneider et Cie (later Schneider Electric) purchased some of the land belonging to Victor Roux and eventually built a munitions/armaments factory close to the shore of the Mediterranean. Initially, its activity was limited to sea trials of torpedoes manufactured in the plants of Harfleur and Le Creusot. To this end, an artificial island made of reinforced concrete, was built in 1908, off the tip of Léoube (Bormes). This is where the first torpedoes made in France were tested.

The people of La Londe called this artificial island the ‘sewing machine’.

The people of La Londe called this artificial island the ‘sewing machine’.

Then in 1912, following

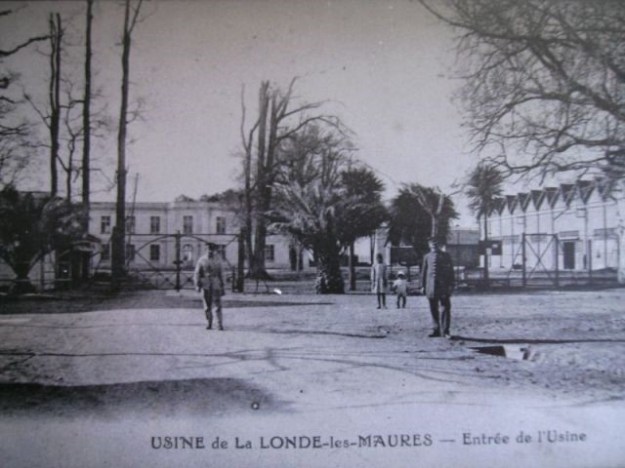

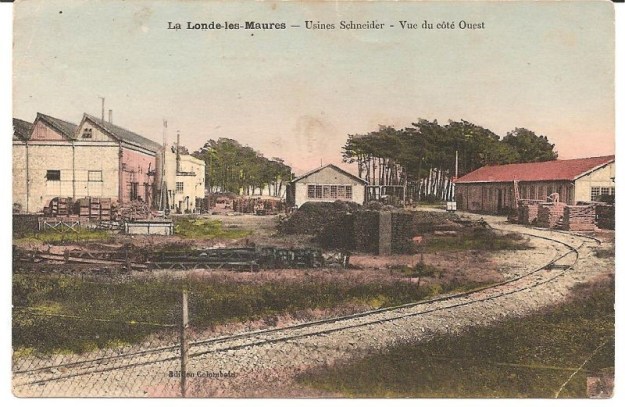

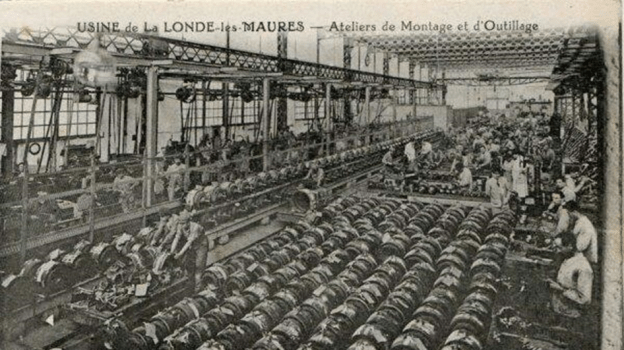

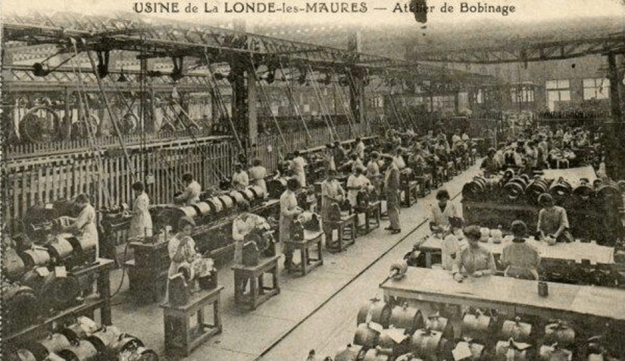

Then in 1912, following  a large order of torpedoes from France and Italy, the design office from Le Havre settled here. A weapons factory was proposed and built. It was an imposing building, near Tamaris beach that would manufacture parts for the army and it was completed in 1913. By the start of the Great War, 234 torpedoes had been made. During the war, the factory mainly made parts for the army (shells, plane parts, etc.) From 1913 to 1920, Henri-Paul Schneider built housing around the factory for his workers; 103 houses and 11 villas in all. The new village was endowed with a food cooperative, a school, a village hall, a post office, a bakery, a bar, public showers and a sports hall.

a large order of torpedoes from France and Italy, the design office from Le Havre settled here. A weapons factory was proposed and built. It was an imposing building, near Tamaris beach that would manufacture parts for the army and it was completed in 1913. By the start of the Great War, 234 torpedoes had been made. During the war, the factory mainly made parts for the army (shells, plane parts, etc.) From 1913 to 1920, Henri-Paul Schneider built housing around the factory for his workers; 103 houses and 11 villas in all. The new village was endowed with a food cooperative, a school, a village hall, a post office, a bakery, a bar, public showers and a sports hall.

People living at Les Bormettes began to have a much better standard of living than people on La Londe les Maures.

People living at Les Bormettes began to have a much better standard of living than people on La Londe les Maures.

Interestingly an Alsatian company called ‘Astrolabe Omininium East’, specializing in film acquired the Castle Bormettes. They were actually a name behind which the German secret service could hide and monitor activity at the torpedo factory. It was expropriated in 1936 and ownership was given to the French Navy.

In the Second World War, the Schneider factory was requisitioned by the Germans when they occupied the Free Zone at the end of 1942, until the allied landing in Provence on 15th August 1944.

In 1972, Castle Bormettes was sold by the Navy, along with the wider estate, to the General Directorate of Telecommunications (today France Telecom) and the Bormettes factory stopped working in 1993.

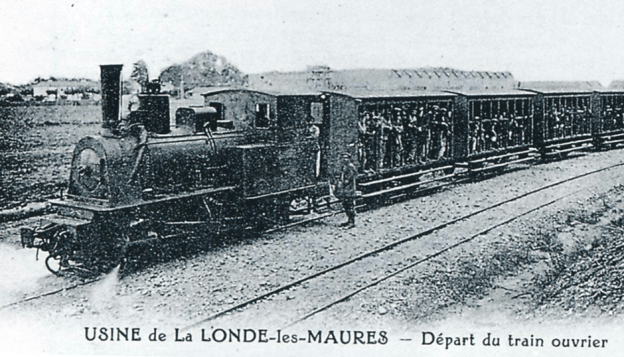

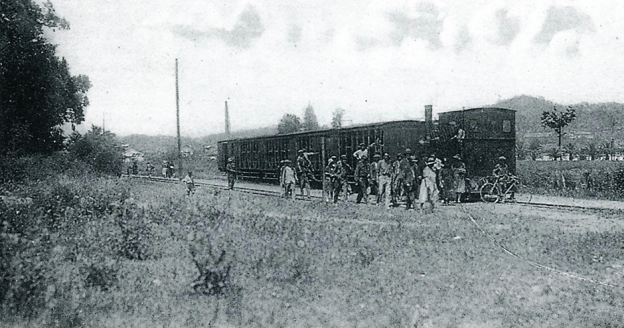

The railway leading to the works is shown in nearby photographs and its formation remains along much of its length as a cycleway named for the people who built it – Promenade des Annamites.

The final images in this post are shared with the previous post which focusses on the Chemin de Fer du Sud de la France main-line. They show images of the factory, part of the village developed for it and the railways that served it.

The last two images in this post are of trains which served the factory. They have both been provided by Jean-Pierre Moreau. The first is a view of locomotive 0-6-0T No. 79 “Luronne” at the head of the workers’ train from the Schneider torpedo factory in La Londe, circa 1921 (Edmond DUCLOS Collection). The second is also of the workers’ train at the entrance of the Schneider torpedo factory in La Londe. The locomotive could be the 0-6-0T Krauss No. 78 “La Madeleine” (Gilbert MARI Collection).

References

[1] http://www.ot-lalondelesmaures.fr/la-londe-cote-terre/le-village-et-son-histoire/les-bormettes.htm, accessed 28th December 2017

[2] Freddy Genot; http://www.cfchanteraines.fr/lvdc/lvdc0149/carnet04.htm, accessed 27th December 2017.

[3] https://www.mindat.org/loc-127375.html, accesses 28th December 2017.

[4] Roland Le Corff; http://www.mes-annees-50.fr/Le_Macaron.htm, accessed 13th December 2017.

[5] Marc Andre Dubout; http://marc-andre-dubout.org/cf/baguenaude/toulon-st-raphael/toulon-st-raphael1.htm, accessed 14th December 2017

[6] Jean-Pierre Moreau; http://moreau.fr.free.fr/mescartes/ToulonGareSudFrance.html, accessed 24th December 2017.

[7] José Banaudo; Histoire des Chemins de Fer de Provence – 2: Le Train du Littoral (A History of the Railways of Provence Volume 2: The Costal Railway); Les Éditions du Cabri, 1999.

[8] Roger Farnworth; Ligne du Littoral (Toulon to St. Raphael) – Part 6 – Hyeres to Bormes les Mimosas (Chemin de Fer de Provence 41); https://rogerfarnworth.wordpress.com/2017/12/30/ligne-du-littoral-toulon-to-st-raphael-part-6-hyeres-to-bormes-les-mimosas-chemin-de-fer-de-provence-41.

[9] Other pictures from all over the internet which are not included in the main text of this post …

Pingback: Ligne du Littoral (Toulon to St. Raphael) – Part 15 – November 2018 Visits to the Line (Chemins de Fer de Provence 81) | Roger Farnworth